LeanLab and Indigo

Indigo participated in the Kansas City LeanLab Accelerator and conducted the following research study in partnership with the Blue Valley Center for Advanced Professional Studies.

Indigo participated in the Kansas City LeanLab Accelerator and conducted the following research study in partnership with the Blue Valley Center for Advanced Professional Studies.

In his book, The End of Average: How We Succeed in a World That Values Sameness, Harvard scientist Dr. Todd Rose examines the idea that there is no average person and that by ignoring individual differences – and what makes us each distinctive – we overlook potential and talent. The End of Average not only shows that there is no average person but also demonstrates the importance of nurturing traits that define each of us

A big part of the work Indigo does is providing schools ‘non-academic data’ that can be used to connect better with students and personalize education. But this begs an obvious question: what the heck is ‘non-academic data’?

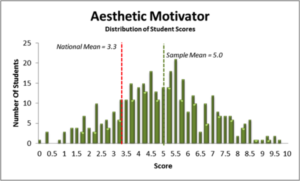

New Motivator Research: Aesthetics Matter for High School Students March 14th 2015, Written by Marie Campbell Indigo recently administered the Indigo Assessment to students at

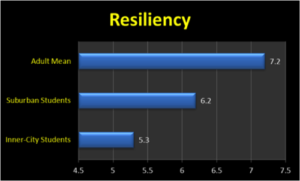

New Research Spots Critical Gap Among Low-Income Students January 28th 2015, Written by Marie Campbell Today’s educators are beginning to understand that student success—that is,

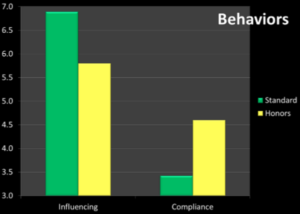

New DISC Research: Need for more Inclusive Honors Section? January 28th 2015, Written by Nathan Robertson Indigo’s primary goal is to improve secondary and post-secondary

aesthetic AI asking awards college fits Communication compliance continuous learning creativity DISC dominance Education empathy Empowering Educators FBLA future of education goals Indigo Indigo Assessment Indigo Data Indigo Education Company individualistic influencing leadership LearnLaunch Listening mentoring Motivators Partners Peak to Peak High School Personalized Learning persuasion planning Podcasts Professional Development self-awareness social soft skills Speaking Engagement steadiness team Teamwork theoretical TTI utilitarian